Tiny Cressona nestles in the Appalachian coal country of southeastern Pennsylvania, about 130 miles directly west of New York City. Its 1,500 residents inhabit one square mile where, on a recent afternoon, traffic backs up in both directions at the borough’s only stop light. Tractor-trailers jack-knife gingerly through a 90-degree turn on the two-lane main route through town. In the 1940s, the government built an aluminum plant here to support the war effort. Alcoa took it over after the war but left in the late 1970s; local business interests resurrected it. Alcoa came back in the 1990s and today runs the plant in partnership with an overseas conglomerate. It is the largest employer in town and sits just down the block from the house on Pottsville Street whose living room I now occupy.

My host, Jane, is president of the Cressona Historical Society. Just shy of 90, she’s a lifelong resident, long retired from teaching in the local public schools. She says she hopes younger residents in the community will start stepping up to support the historical society, whose active membership is – well, dying off. This doesn’t seem likely to me. As with a lot of small towns, the coming-of-age generation is preoccupied with modern life, worrying that progress will brush right by if it dares look back. Jane’s small, tidy house lies on the main drag. Trucks trundle by a dozen paces from where I sit, their low rumble periodically droning out the ticking of a grandfather clock that hulks in a corner of her comfortable but cramped living room.

I’ve sought her out for a bit of local history, of course. Cressona, she recounts, is named for John Chapman Cresson, a civil engineer and president of one of the private railroad companies that sprang up to move this region’s most prized asset – high-grade, cleaner-burning anthracite coal – to market. In the mid-19th century, rail would come to supersede the canals that were the initial paths of commerce in the region. Anthracite – harder, shinier, more valuable than bituminous coal (all the info you could possibly want) – is still mined in the area today. For nearly half a century it has fueled an out-of-control mine fire beneath the once-prosperous borough of Centralia, now deserted and uninhabitable, about 14 miles northwest of here as the crow flies.

The railroad interests themselves, Jane tells me, couldn’t be listed as landowners at the time of Cressona’s founding in 1857. So Cresson was listed as the owner of the lands the railroads bought up. Coal drew the railroads. Railroads built the town. Immigrants, the largest pool of them German, built the railroads. That last might hint at why I’m here, three hours and a century and a half from home.

At the start of the week I am in Alexandria outside Washington to meet my sister, who has lung cancer, and go with her to see a specialist at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. Before I drive down, she and I speak about doing something a little more diverting than usual during my two-day stay – earlier visits have almost exclusively featured waiting rooms for chemo, radiation, a consult etc. We settle on taking a 70-mile drive out to the Civil War battlefield of Antietam in western Maryland – named by Union custom for the nearest water feature, the creek that figured so decisively in the battle. The one-day engagement – it was called the Battle of Sharpsburg by the South, for the nearest town – remains today the single bloodiest day in American history, with a total of 23,000 men injured, gone missing, captured or killed.

In that unfortunate last number is an ancestor on my father’s side – George, younger brother of my great-great grandfather, Henry – felled by Confederate artillery fire that September day in 1862, 101 years, less a day, before I was born. Another Dentzer brother, John, twice ran off to enlist but was turned away for being too young. At last accepted in 1863, he served ably for nearly two years before he too was killed, three months’ shy of the war’s end. Before the week is out, I will have stirring encounters with their ghosts in the rolling farmland of a onetime battlefield, and in the rural backcountry that is so much of America. It will call to mind once again how even ancient stories inform and clarify my own – how the past ineradicably shapes both present and future, even if banished to some dark attic of memory.

When war broke out in April 1861, Abraham Lincoln, believing like most that the conflict would be short-lived, called for 75,000 troops on a three-month enlistment. The first five companies to muster and arrive in Washington came from the Pennsylvania region where my German immigrant ancestors settled around 1840. By the time those early enlistments ran out, it was clear the war would be neither a Northern rout nor a brief affair. Lincoln called for 300,000 troops to serve three years. The 48th Pennsylvania Infantry, organized by James Nagle, who had raised and led regiments in the Mexican War and the early days of the present conflict, mustered in on Oct. 1, 1861, 23-year-old George Dentzer, now a private in Company K, among its ranks.

George, according to records I found on this trip, came with brother Henry and their mother, Catharine, from Bavaria in 1841, leaving the French port of Le Havre on the English Channel aboard a ship named the Sully (first records said Sally) that arrived in New York in late April. Their father, Johann Friedrich, a carpenter, had come alone two years prior. The family lived in Pottsville, now the county seat of and only city in Schuylkill County, about three miles from where Cressona would later rise. Pottsville is home to America’s oldest brewery, and Henry Dentzer worked there, late in his career, as chief engineer. George was three and Henry five when they arrived in America. Their younger brother would be the first of my paternal lineage born in the U.S., in October 1843. He was given his father’s Anglicized name, John Frederick. The 1850 census lists those Dentzers plus four-year-old Catharine, named for her mother, living in Pottsville’s south ward. (My mother’s family settled in Connecticut from England in the 1640s, relocating to Vermont in 1791. Ancestors on that side also served in America’s wars, but that’s another story.)

George, at his enlistment in 1861, resided in Cressona. Records of the regiment, which before last week my family had never known of, list him as 5′ 8 1/2″ tall with dark hair and complexion and gray eyes. He gave his occupation not surprisingly as “railroader”; an outdoors laborer enlisting in early fall, perhaps toil in the summer sun was behind his dark complexion. Online records that volunteers at the Schuylkill Historical Society in Pottsville later help me find show two enlistments for a John Dentzer, also of Cressona, prior to 1863. One shows no disposition of his service record and another that he was “dropped from the rolls.” I wonder if these might be John’s two failed enlistments. When finally he does enter service with the 48th Pennsylvania on Jan. 19, 1863, he is 19 years old and stands just 5’4″, also with gray eyes and dark hair but of light complexion (it was midwinter after all). He listed his occupation as seaman – odd for someone living in a landlocked county, but it might signify that he worked on one of the area canals.

By the time John enlisted, his older brother George had been dead 16 months. John served longer and saw more combat, was promoted to corporal. He fought at several of the more famous battles of the war – Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor, where he was wounded in June 1864. After that bad Union defeat, Grant’s army laid siege to Petersburg, and it was there that John’s 48th Pennsylvania Infantry commenced the undertaking for which it is best known: the digging of the Petersburg mine.

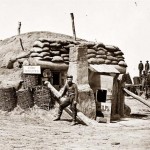

It was an ingenious but ultimately ill-fated Union attempt to pierce the Confederate defenses and end the siege. The explosion set off on July 30, 1864 became known in the South as the Battle of the Crater. After holding an early advantage, Union forces were routed. Eight more months of siege followed, with the opposing forces daily lobbing various types of ordnance at one another. John Dentzer hunkered down at Fort Sedgwick, one of nearly three dozen makeshift Union forts that sprang up around Petersburg during the siege. It lay closest to the Confederate lines and was thus subject to more than its share of shelling; Union soldiers nicknamed it Fort Hell. John was killed on Dec. 28, 1864 when a Confederate shell scored a direct hit on his fortified shelter, or “bombproof.”

Some of this we knew already from histories written or compiled by my grandfather and great-grandfather, both newspapermen who lived in western Pennsylvania outside Pittsburgh. I remember as a kid poring over two albums my grandfather assembled for us. These included a several-page family history tapped out by his father along with dozens of old family photos, including pictures of the brothers killed in the war. My father advanced the family history considerably; later my sister Ardith, the one I am visiting, took up the task. Back in Alexandria, after she and I finalize our Antietam plans, I do some quick online searching and find without much effort some detailed information on the Dentzer brothers and their regiment, much of it from a Schuylkill County-born historian who has long studied the 48th PVV, as it is known, and hosts a blog on the regiment. I don’t, at the time, take note of his name.

The visit at Johns Hopkins, on Monday last, goes pretty well. Ardith gets treatment at Georgetown University and the purpose of this trip is information gathering and comparing – do the JHU specialists have a different view of her treatment options. On the drive back from Baltimore and again the next day en route to the battlefield she goes on in her fashion about distant relatives whose names I have never heard and will doubtless not recall. She delves into prosaic anecdotes about their lives, arriving periodically at her characteristic “long story short” transition, the phrase being a clear sign, of course, that the story is nowhere near its conclusion. She is enthusiastic about the trip and insists on bringing a copy of the Civil War page from my grandfather’s album to show the park staff at Antietam. I don’t think much of the idea; it seems akin to bringing one’s own watercolors to the Met. After an hour in the car out to the battlefield, I blow my stack at her when she offers for the umpteenth time directions I haven’t asked for. My regret is instantaneous. She goes quiet for a minute and then, after my third apology, remarks how hurtful my outbursts can be. Growing up in a family of five kids, it was de rigueur for us to lash out at one another more viciously than we might at a real enemy. For most of this last decade, until she was diagnosed, she and I barely spoke, but only because I ignored her entreaties, attempts to engage or connect. That is another story too. In the car, pushing through the thick, damp summer heat of western Maryland, we recover from the road-rager-yells-at cancer-patient incident and soon arrive at the visitor center.

The Antietam battlefield covers more than 3,200 acres – 5 square miles – the battle itself lasting more than 12 hours from predawn to sundown. We plan to watch a short film and then take the recorded driving tour of the main engagements: Miller’s cornfield, which changed hands more than a dozen times during the battle; the East and West woods, where nick-of-time counterattacks at different times by both sides saved the day for their respective forces; the Sunken Road, a rutted farm lane that would become a mass grave, more or less, known for all time as Bloody Lane; a modest bridge over Antietam creek, christened in blood for Union Gen. Ambrose Burnside, whose superior forces a small Confederate band held off for three hours; and finally, the end-of-day Confederate attack on Burnside’s advancing line after the bridge was taken. These last two engagements, we know already, were where George Dentzer’s regiment had fought.

Our carefully planned assault, however, will soon be outstripped by changing circumstances on the field, as it were. As we purchase our park pass, Ardith pulls out the photocopied scrapbook page to show the rangers at the front desk. She identifies the two boyish men in the photos, one a casualty at Antietam. One of the rangers asks his unit, and when I tell him, he goes wide-eyed. “Oh! You need to wait right here,” he says. “We have a ranger you have to meet – that’s his regiment. He’s been studying it for years.” Off he goes, returning shortly with the man in question.

As the second ranger approaches, I see him glance at the photocopy on the counter and read the names below the pictures. He steps back, visibly moved, looking like he’s fighting back tears. Seeing this, my sister tears up also. (I don’t – maybe for once.) Regaining his ranger comportment, he steps back to the counter we are standing over and tells us he’s a native of Schuylkill County and has studied the 48th for 20 years. He has visited the Dentzer boys’ graves often. They are buried side by side in their hometown of Cressona. (The now-defunct G.A.R. post in Cressona, predecessor to the American Legion, was named for them.) On those visits, he tells us, he’s wondered about who they were, where they came from, how they must have looked. With an off-color photocopy of two faded family photographs, captioned with a couple of lines of text from my grandfather’s typewriter, we have just answered questions he has pondered for years.

I have been to those Dentzer graves too, though I scarcely remember. At the time, in the full onset of adolescent ennui, I didn’t care much. More than 30 years ago, as my parents dragged us once again across that Sahara-like ribbon of asphalt known as Interstate 80 to visit relatives in western Pennsylvania and Ohio – this was what passed for summer “vacation” in those days – we had stopped in Cressona and neighboring towns to trace our forefathers’ footfalls. George initially was buried at Antietam. In the weeks or months after, his older brother, who stayed out of the war to care for their mother (we don’t know what happened to their father), took a wagon to the battlefield 140 miles southwest of Cressona to collect his brother’s body and bring it home for burial. We don’t know – yet, anyway – how John’s body was returned, though his headstone notes, matter-of-factly, that his remains “were brought home at the expense of his mother.”

We tell the ranger parts of these tales and he in turn begins to recount – in riveting, staccato detail, like skirmish fire – what likely happened to our ancestor in the afternoon leadstorm west of Burnside’s Bridge. Our chance meet-up with him, he tells us, is his most memorable day at the battlefield. From the shelf behind him he pulls a copy of a book he has written on the regiment. I take note of his name, John David Hoptak, and when he mentions his blog I recognize him as the online author I was reading the night before. He has a master’s in history from Lehigh, has written two books, has a third in the works. We listen, rapt, as he spins the story. Then he tells us he’d love to take us out to the battlefield to show us where the 48th fought. It would be an honor, he tells us. But the honor is all ours.

John gets another ranger to fill for him on an upcoming tour and we follow him out in our car to the heights above the stone span that, before the battle, was known as the Rohrbach bridge. Antietam Creek is about 75 feet wide here, at the bottom of a ravine. Bridge approaches on both banks parallel the creek for a good distance. Advancing Union troops were thus exposed to heavy, accurate fire from the well-dug-in Confederates. I have posted the complete video of the tour he gave us along with the excerpt below, so I won’t recount every word. Listening to his narrative, looking down at the bridge from what had been the Confederate-defended west bank, it is easy to conjure up the picture of our ancestor’s regiment massing on the opposite bank, laying down covering fire for the regiments that advanced repeatedly on the bridge until it was taken. Once it was, hours went by – a critical delay – before the Union forces could again press forward. That allowed time for a large Confederate force to arrive from Harpers Ferry and begin to roll up the Union flank in the final attack of the day.

As the sun was setting, the men of the 48th, including George Dentzer’s Company K, were ordered to the front to relieve battle-weary regiments nearly out of ammunition. Under withering artillery fire from Confederate guns half a mile away, they advanced the last hundred or so yards on their bellies before reaching the line – a sunken lane on what was then a field owned by farmer John Otto. The property – we are standing on it now – was only recently purchased by the park service and added to the official battlefield. (Because of this, the official monument to the 48th, erected in 1904, stands some 500 yards away, by the Confederate line.) We look west toward where the Confederate batteries would have stood, imagining the setting sun’s glare and the long shadows that confused the Union’s line of sight, and John tells us we are standing very near the spot where George Dentzer likely fell, almost certainly hit by artillery. At battle’s end, his body would have been collected and buried, perhaps by a stone wall next to Burnside’s Bridge a few hundred yards to the rear. Wood slats attached to the bridge, used to divert water, were removed and used as makeshift headstones. Maybe this is how and where Henry found his brother when he came to collect his body.

We leave Otto Farm Lane, return to our cars and drive to the 48th PVV memorial. There, we look back from the area of the Confederate line across the hilly landscape. In the distance is the split rail fence next to the lane where our ancestor fell. My video camera has run out of juice; too bad, because John’s narrative continues to rivet us. After pictures with our guide, we return to the visitors center and Ardith and I take our leave – a two-hour driving tour still awaits. When we reach Burnside’s bridge for the second time, I walk down from the heights and cross to the bridge to stand by the stone wall that gave cover to the Union soldiers and, later, marked their graves. A Napoleon cannon stubbornly guards a field of waist-high grass. So still here now, eternal. That night, John will post an account of our visit on his blog, calling it “an extraordinary day.” We feel the same. He emails photographs of the regiment along with a spreadsheet of enlistment records. I’ve told him I’m side-tripping through Cressona on the way home to New York and he directs me to records I can review in Harrisburg, the state capital. (As things happen, I have to bypass Harrisburg, but I’ll likely be back.) I tell him in an email how important his work is, preserving this history and the memory of these sacrifices, still so relevant to American democracy.

I leave Alexandria the next day and get to Cressona in late afternoon after some emergency car repairs. After trolling around the tiny town for half an hour, I still haven’t found the damn cemetery – it’s not on maps, doesn’t come up on an internet search, but I can find it, I… can… find it! I turn up a short sidestreet where a couple tow-headed boys are riding bikes in front of me. I have to slow and as I approach I see a group of four or five men in their late teens or 20s kicking back around a few parked cars, a few drinking beer out of mason jars. They walk toward me and – yes, it looks like I’ll have to ask directions. I tell them what I’m looking for, and collectively they guide me. It is about half a mile away, up a hill on the other side of the main road. I pull away taking note of one in particular, covered in dirt, or maybe it’s coal dust – not sure. I think again of what different worlds we live in.

I reach the cemetery in moments. I know from my mother’s notes of that previous visit that the brothers are buried near a flagpole. There is only one flagpole in the cemetery and I find them easily. The writing on their headstones is worn now and virtually indecipherable – 30 years ago, on that earlier visit, it was still legible, and my mother wisely wrote down the inscriptions, taking care to do so exactly as they appeared:

The bible verses cited on their head stones are both from the Old Testament, George’s from Psalm 55:18:

a

He ransoms me unharmed

from the battle waged against me,

even though many oppose me.

a

John’s is 2 Samuel 1:23, David’s lament upon the death of King Saul and his son, Jonathan, David’s friend.

a

Saul and Jonathan—

in life they were loved and gracious,

and in death they were not parted.

They were swifter than eagles,

they were stronger than lions.(New International Version Bible)

a

I look these up later. Standing at the cemetery, I feel like I’ve been dropped into a Ken Burns documentary. It is dusk, hot and humid, the air still, the chirp of cicadas like a thick white noise, no-see-ums nibbling. I am alone in the cemetery with my ancestors, watching darkness gather and wondering why I’m here, why people sometimes find in themselves a desire to know their ancestors better. In my case – out of work, mostly by choice, just over a year – maybe I’m looking to some part of my heritage, my past, to recalibrate the present and somehow divine the unknowable future. I think about my sister’s illness and her own uncertain future – she hardly seems sick at all, though scans of her insides show different.

I wonder here what drew two boys from a German Lutheran immigrant family to enlist in the Union cause, like thousands of other men. A chance at glory? Excitement? A sense of duty? It seems somehow overly romantic to believe they were motivated by ideals alone. Am I too cynical? And why is it, by the way, that this epic struggle, still the defining event in our history, 145 years after, carries so much more immediacy than those present-day conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq? Yes, it was our family war – everybody knew everybody.

Before Antietam, the sole Northern cause was: preserve the Union. The battle, a tactical draw, was a strategic victory for the North. The Federals had stopped Robert E. Lee’s first foray into northern territory and given Lincoln the “victory” he needed to ennoble the Union cause with the Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln announced it five days after the battle. Thus pledged to end slavery (albeit with shrewd conditions), the Union effort could now not possibly be undermined or opposed by foreign powers, Britain chief among them, that had Confederate sympathies. Slavery would not be officially abolished until passage of the 13th Amendment after the war, but the Proclamation effectively foretold an inevitable Union victory, though still more than two years off.

Over the three days I spend traipsing through rural battlefields, record rooms and small town cemeteries, I come back often to how applicable this is to present day. OK, maybe each generation tends to overplay the significance of the times in which it lives, but I am clearly not alone in my distress over the direction this country has veered in my lifetime, and how our nation’s intransigent, multilayered divisions, however unlikely to lead to imminent bloodshed, have nonetheless gutted our democracy. I happen to think that a sizeable segment of my fellow citizens are 100 percent wrong about any topic I can think of – social policy and justice, matters of law, constitutional freedoms, governance, taxation, healthcare, public finance, defense, civil liberties, education, energy, the environment. Doubtless they think the same of me. These divisions are easy to exploit for political gain – fears and prejudices played to and preyed upon, faith in leaders undermined by innuendo or by their own failings, ignorance perpetuated by a sclerotic educational system, opportunities and savings shriveled by financial crises beyond our understanding, the vox populi drowned out by special interests, our fundamental equality increasingly a mirage behind ever-worsening economic divisions, our pursuit of happiness reduced to a sprint just to stay in place. We don’t do battle with weapons. We skirmish with beliefs and ideologies, many contrived for maximum political effect – fear-mongering and discriminatory immigration laws, bans on gay marriage, a throng of disaffected who grossly misunderstand our founding history, tax breaks for the richest among us, a conservative high court systematically dismantling decades of progressive jurisprudence. There isn’t a single main fault line in this country, there are many, small and large. And as these grind against each other, we are paralyzed to address the universal issues on which there should be ready consensus – education, health care, climate change, energy – or we arrive at shortsighted, politically expedient compromises that push responsbility down the line to future generations.

This sounds like so much hand-wringing. I watch this impending train wreck from a safe distance – loath, I have to admit, to climb on board and help look for the emergency brake. Are we just a little wobbly, like a punchdrunk boxer, or are we close to stumbling, or being stampeded, off a cliff? Are we witnessing a new birth of bigotry, ignorance and intolerance? Maybe, as at Antietam, there is a galvanizing battle ahead that will lend justification for a new and ennobling higher cause.

I am, of course, not the first to be thus stirred after a stroll on a Civil War battlefield. It’s the potential universality of that experience that maybe is cause for hope. That my ancestors were infantry – cannon fodder – leaves me just as moved as if they were regiment-saving heroes. They were soldiers among soldiers, following orders, supporting comrades and their cause, not for the $13 a month they earned, but because they believed it was the right thing to do. These men, newcomers to America, were more vested in their country’s well-being than most of us have time or interest for, and I put myself at the head of that line. When our story is written, will it say we sacrificed and struggled for our beliefs and for the noble causes Lincoln and others in our history have so movingly espoused? Or will we – will I – be labeled deserter – disinterested, self-absorbed non-combatant?

When the call goes out, if it hasn’t already, will I pass muster?

When I visited Antietam while on a bike trip, the wheat was moving gently in the breeze – wave on wave approaching the sunken road. Antietam then was almost bare of anything of the battle except for a few small signs. The next day onto Gettysburg where my brother exloded in anger at the “Robert E. Lee Fast Food” kind of places that desecrated the park.

We returned toi my sister’s ion Alexandria, where Nancy called to tell me she had been diagnosed with breast cancer.