Cleatus is my new best friend here – ok, at the moment he’s my only friend here, that being about 20 miles east of Glide, Oregon in the Umpqua National Forest. He looks mid 30s – I forget to ask because I’m a little preoccupied just now, for reasons I’ll explain – but I do pick up that he makes $9 an hour driving a tow truck. He’s on call 24/7, gets days off here and there but they have to be planned well in advance, so other drivers can cover. He and his wife, Breezy, who works as a dental office receptionist, have a 14-month-old girl, Rebecca. They are planning a trip to the Oregon coast, a couple hours’ drive west. It will be their first such trip in four years.

Like me, Cleatus was named for his father, who was named for his father. He’s Cleatus III. Sounds like a pope, or a Roman emperor (holy or pagan). But the name is Southern in origin, he tells me. His grandfather lit out for California from the Missouri Ozarks at 14, fed up with the routine beatings doled out by his stepmother. Cleatus I married there and had two kids. Later, he married a second time to a woman with three kids, and they had three more. They came to this area, all 10 of them, in the early 60s, Cleatus tells me. That was a few years after The Blast. I’ll get to that presently.

Cleatus used to have a better job that paid $20 an hour with benefits, profit sharing and the like. He worked for North River Boats until April 2008, when he got laid off along with 100 other workers. Fifty-four more layoffs came that November. Last April, the FBI served a search warrant on the company and seized computers and other records. Five days later, the company’s owner and president was accused of illegally inflating inventory reports and invoices to obtain bank financing, defrauding Wells Fargo of $3.3 million. He’s in jail now, but not for the fraud. Last September, on a public beach in Long Beach, WA, in broad daylight, police on foot patrol watched as he pumped three shotgun shells into his longtime girlfriend, killing her. The man sobbed at his preliminary hearing two days later, where a prosecutor recounted how, after administering the coup de grâce, the shooter looked directly at the officers, dropped the gun, then threw his hat in the air in agitation. Quickly met by three officers, he was arrested without a fight. He is now being held on $50 million bail awaiting trial for blasting his girlfriend. But that’s not the blast I’m talking about. (A timeline to the whole sordid saga.)

I first hear about The Blast from Ken at The Mobile Tune as we talk about Oregon unemployment (at 15 percent here in Douglas County, down from a high of 18.5 percent a year ago), the logging industry (moribund), sustainability (a study in diminishing returns, in Ken’s view), and how he first came here. By here, now I mean Roseburg, the county seat. It is Tuesday morning and I should be somewhere in Idaho by now. So in addition to being out of time, I am also out of place, but I’ll come to that in a moment, too. Ken was living in the Valley outside Los Angeles in the early 70s, when the smog was so thick, he says, you tied a string from your front door to the door of your car to find it each day. He left and came to work for a car dealership here. After a few a months, fed up with how the place was run, he started his own emergency auto repair shop, whch is why I am in Roseburg, why I know Ken, and why Ken is now rivaling Cleatus for status as my regional BFF.

I first hear about The Blast from Ken at The Mobile Tune as we talk about Oregon unemployment (at 15 percent here in Douglas County, down from a high of 18.5 percent a year ago), the logging industry (moribund), sustainability (a study in diminishing returns, in Ken’s view), and how he first came here. By here, now I mean Roseburg, the county seat. It is Tuesday morning and I should be somewhere in Idaho by now. So in addition to being out of time, I am also out of place, but I’ll come to that in a moment, too. Ken was living in the Valley outside Los Angeles in the early 70s, when the smog was so thick, he says, you tied a string from your front door to the door of your car to find it each day. He left and came to work for a car dealership here. After a few a months, fed up with how the place was run, he started his own emergency auto repair shop, whch is why I am in Roseburg, why I know Ken, and why Ken is now rivaling Cleatus for status as my regional BFF.

I pass through here Monday night on Route 138 and am about 40 miles east on my way to Bend, my destination for the night. It is raining on and off as it has been since I finally made the turn east to leave the coast, gazing for the last time on the Pacific Ocean in Bandon a few hours earlier. Driving all day, I have about 2 1/2 hours to go before Bend but am still alert. The scent of the air in this land of federally protected Ponderosa pine is really, well, delicious. Moist but fresh, like it’s been scrubbed clean. Fertile, peaty and slightly sour but mushy sweet also, like a day-old sticky bun. I roll down my window to get another whiff, hoping better words will come to me to describe it. I look back to the road and there it is, a brown stony lump in the roadway. I’ve been driving along this two-lane road for 25 miles since the last outpost of human activity, have seen only a handful of oncoming cars and none heading with me. It is 8:30 and pitch black except for the throw of my headlights, which is now lighting up the 40-pound rock I’m about to run over. My thought process, slowed down oh maybe 2-1/2 times to capture every nuanced realization, goes something like this:

“Wow what amazing smelling air wait what is that in the road an animal no I’ve been watching for them expecting a moose what’s the plural of moose it’s still moose right it’s a rock like a boulder just smaller can I swerve no room no can I clear it maybe what’s the highest part of my…” BAM. Another blast. So much for fresh air being good for you.

I’m still moving. What just happened? The car’s engine is suddenly so loud it feels like it’s reverberating through my sinuses, so I think (hope) it’s just the muffler. I’m a little dazed, a little in denial. For a minute I think I can keep going, because really this can’t possibly be happening here in the middle of nowhere, at night, in the rain, with no cellphone service and none for the last 15 miles? I’ve already driven something like 5,000 miles without incident. It’s just loud, right? OK? Uh, no, it’s really not OK. Motherfucker.

There is no shoulder right here. I pull over as soon as there is and as I do the car shuts itself off. I turn the ignition off then on again just to see if it will restart and for a moment the lights go out. It is really fucking dark here. I can barely make out a craggy rock face on the left – I can’t see how tall it is. On the right, I see the first few rows of probably a million or so trees that blanket the Hundred Valleys of the Umpqua river. I hear a rushing stream. The car starts but immediately shuts down again. Common sense returns about this time and I realize I might do serious damage if I keep trying to start it.

There is no shoulder right here. I pull over as soon as there is and as I do the car shuts itself off. I turn the ignition off then on again just to see if it will restart and for a moment the lights go out. It is really fucking dark here. I can barely make out a craggy rock face on the left – I can’t see how tall it is. On the right, I see the first few rows of probably a million or so trees that blanket the Hundred Valleys of the Umpqua river. I hear a rushing stream. The car starts but immediately shuts down again. Common sense returns about this time and I realize I might do serious damage if I keep trying to start it.

I shut off the radio, the ventilation, anything else with a switch but leave on the lights and flip on the hazards. I pop the hood and the hatch, get out, grab a flashlight from the back and, coming around to the front, lift the hood and peer in with the flashlight. Nothing obvious. There is a little steam and the familiar smell of my slow coolant leak and dirty motor oil. I kneel down on the wet pebbled shoulder and look underneath. There, I see oil dripping from what used to be my oil pan but which now looks more like a pillbox that’s been ripped open by mortar fire. I start figuring the cost of this – tow, new part, shipping, labor, hotel for two days, at least. And still I have to get myself and the car out of here and back to town. Worse, I wonder if I’ve killed my car. Without oil in the engine metal parts heat up from friction and the engine seizes. I changed my oil and filter in Alamogordo, maybe 1500 miles ago. With latent gearhead tendencies, I have used a higher grade synthetic in the car for years. Later, the tow truck driver – Cleatus, my Best Friend For Now – posits that it might have saved me from more serious, near instantaneous damage.

I wonder how long I’m going to be stuck on the side of the road here and try to remember whether bears are prevalent in this part of Oregon. It’s been maybe five minutes and I wait another five, then maybe another. It’s hard to calculate. But then I see headlights behind me. I’m lucky – it easily could have been a two-hour wait. I put my hazards back on and wave my flashlight like I’ve seen train signal workers do, up and down, slowly. The car stops. Rick and Phyllis, who work at Diamond Lake Resort about 40 miles from here, are returning from a day visit to Rick’s mom on the coast. They take me on board their SUV and we start heading east, but when we parse it out, Rick says it makes more sense to go back the other way, towards Glide, which is about the last place I remember having phone service. They drive me all the way back, 25 miles out of their way, to a gas station there. Here I have signal and a place to stand out of the rain. A sign I saw earlier while passing through here has stuck with me – towing by Clyde from Glide. (Yes, advertising works.) I start to look up the number on the phone – addicted to tech – but then the service station worker just gives it to me. Rick and Phyllis head off. Later, as Cleatus and I drive to get my car, he gets word of a larger rock slide on the same stretch of road. We see it when we get to my car, just a couple hundred yards ahead of where I pulled over. Road crews are clearing it. (The next day, I send Rick an email to thank him again and I ask if he and his wife ran into the slide. They did, he replies, but it got around it without much trouble.)

Seeing the other slide makes me feel a little better – like I’m not the victim of a conspiracy (perpetrated by whom exactly? A road-hating wilderness anarchist? A vengeful beaver?) Rick and Phyllis, and now Cleatus as we drive back to Glide, car in tow, recount the forest fires of last summer (seen from space), set off by lightning, that scorched the rocky ridge above this road. Its soil loosened, the ridge is much more susceptible to slides, especially when it rains. All three tell me they’re grateful for the rain, save for the misfortune it has brought me. It has been an unusually dry, unusually warm winter, Rick says. The snow pack at Diamond Lake should be five feet this time of year; it is two. Without winter snow there will be less water through next summer for irrigation, maybe for fighting or preventing fires. Phyllis brings up global warming, and while I’ve read that such year-to-year anomalies don’t necessarily figure as manifestations of the irrefutable long-term warming trend, I think about the same thing, and again the next day when, here in mid-February, I see trees in full blossom, the temperature topping 60 degrees.

Seeing the other slide makes me feel a little better – like I’m not the victim of a conspiracy (perpetrated by whom exactly? A road-hating wilderness anarchist? A vengeful beaver?) Rick and Phyllis, and now Cleatus as we drive back to Glide, car in tow, recount the forest fires of last summer (seen from space), set off by lightning, that scorched the rocky ridge above this road. Its soil loosened, the ridge is much more susceptible to slides, especially when it rains. All three tell me they’re grateful for the rain, save for the misfortune it has brought me. It has been an unusually dry, unusually warm winter, Rick says. The snow pack at Diamond Lake should be five feet this time of year; it is two. Without winter snow there will be less water through next summer for irrigation, maybe for fighting or preventing fires. Phyllis brings up global warming, and while I’ve read that such year-to-year anomalies don’t necessarily figure as manifestations of the irrefutable long-term warming trend, I think about the same thing, and again the next day when, here in mid-February, I see trees in full blossom, the temperature topping 60 degrees.

It’s not long into my conversation with Ken the next morning that we come around to climate (ref. the smog of LA), not to mention logging, sustainability and Oregon’s anemic economy. By now we’ve looked at the underside of my car and yes, phew, it looks like just the oil pan. I order a used one from my reliable Saab used parts place in upstate New York. It will be here tomorrow morning, Wednesday. With luck I’ll be back on the road by late Wednesday afternoon, a layover of less than two days.

It’s not long into my conversation with Ken the next morning that we come around to climate (ref. the smog of LA), not to mention logging, sustainability and Oregon’s anemic economy. By now we’ve looked at the underside of my car and yes, phew, it looks like just the oil pan. I order a used one from my reliable Saab used parts place in upstate New York. It will be here tomorrow morning, Wednesday. With luck I’ll be back on the road by late Wednesday afternoon, a layover of less than two days.

I picked Ken’s shop at Cleatus’s suggestion and there’s an inexpensive hotel right next door, the Douglas County Inn. It’s 12:30 am when I get settled there. I see the lights of the Denny’s I passed coming into town oh so many hours before and head for it on foot, crossing the South Umpqua river and looking up at a lighted cross on a hill that I later learn is Mount Nebo, home of the world famous weather-forecasting Mount Nebo goats (you’ll have to read about them here or here on your own). My luck today dictates that tonight Denny’s has closed the kitchen early for its monthly deep cleaning. All they have is soup, chicken or cheesy broccoli. Pass. Walking back across the river, I look at the cross again. The lights on its left arm are out. So the town is religious, Christian, but not born again, has faith but is not fanatical. I’m staying in a land of the one-armed cross. How bad can that be?

Ken is 65 and has that piercing, seen-it-all wit of a longtime successful independent businessman who’s suffered a lot of fools in his day. As we talk, the phone rings and he fends off a string of them – no I don’t need that, you called here yesterday too trying to sell me on it. Yes yes yes your car will be ready soon as you need it as long as you don’t need it before Friday, etc. He’s a straight-shooter though. The state’s economy is still tanking, he says, worse than most of the country. I look it up later and Oregon is one of 10 states where unemployment is still above 10 percent. Logging is the main industry still – Oregon does more of it than any other state. But environmental regulations, regardless of where you stand them, have unquestionably hurt the industry. As home construction stalled, so did the need for lumber, making things worse. I find a brief history of Oregon logging online later and read every word. Ken’s son is a green logger, he says, and they disagree about clear-cutting vs. sustainable harvesting. Ken cites the high unemployment and casts things in social terms, i.e., if people are out of work, out of money, what’s the human toll? How sustainable is that? As if to drive the point home, a woman arrives in a pickup to deliver car parts. She looks at least 10 years past retirement.

Ken is 65 and has that piercing, seen-it-all wit of a longtime successful independent businessman who’s suffered a lot of fools in his day. As we talk, the phone rings and he fends off a string of them – no I don’t need that, you called here yesterday too trying to sell me on it. Yes yes yes your car will be ready soon as you need it as long as you don’t need it before Friday, etc. He’s a straight-shooter though. The state’s economy is still tanking, he says, worse than most of the country. I look it up later and Oregon is one of 10 states where unemployment is still above 10 percent. Logging is the main industry still – Oregon does more of it than any other state. But environmental regulations, regardless of where you stand them, have unquestionably hurt the industry. As home construction stalled, so did the need for lumber, making things worse. I find a brief history of Oregon logging online later and read every word. Ken’s son is a green logger, he says, and they disagree about clear-cutting vs. sustainable harvesting. Ken cites the high unemployment and casts things in social terms, i.e., if people are out of work, out of money, what’s the human toll? How sustainable is that? As if to drive the point home, a woman arrives in a pickup to deliver car parts. She looks at least 10 years past retirement.

*/ 400w, https://billdentzer.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/02/trucks1-200x300.jpg 200w" sizes="auto, (max-width: 288px) 100vw, 288px">Ken says selectively cutting and replanting trees reduces the ecodiversity of the forest, whereas clear-cutting and leaving things to regrow on their own does not. (I don’t know enough about these things to challenge, but I think to myself I am much closer to his son’s way of thinking than to Ken’s.) The quality of wood now offered for sale is crummy as well. He recounts how an old-timer once sheepishly told him that the mills he used to work for burned as fuel the grade of lumber that is now sold for construction – any wood, that is, with knots. Ken says he was remodeling his home some years ago and found that only the wood beams with knots in them were damaged by The Blast, and here’s where I hear about the worst event in Roseburg history, and one of the worst ever in the state.

*/ 400w, https://billdentzer.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/02/trucks1-200x300.jpg 200w" sizes="auto, (max-width: 288px) 100vw, 288px">Ken says selectively cutting and replanting trees reduces the ecodiversity of the forest, whereas clear-cutting and leaving things to regrow on their own does not. (I don’t know enough about these things to challenge, but I think to myself I am much closer to his son’s way of thinking than to Ken’s.) The quality of wood now offered for sale is crummy as well. He recounts how an old-timer once sheepishly told him that the mills he used to work for burned as fuel the grade of lumber that is now sold for construction – any wood, that is, with knots. Ken says he was remodeling his home some years ago and found that only the wood beams with knots in them were damaged by The Blast, and here’s where I hear about the worst event in Roseburg history, and one of the worst ever in the state.

What is now Roseburg began life, in white settlement terms, as Deer Creek in the 1840s. In 1851, Aaron Rose, a Jew originally from Ulster County, NY, settled here and opened a roadside inn. Later he donated land and money to build a courthouse. The town was named Roseburgh for him in 1857. The ‘H’ went away in 1894.

At one time Roseburg was known, at least in these parts, as the timber capital of the world. Hundreds of trucks carrying logs rolled through each day. Now the number is maybe a couple dozen, if that. The town prospered through most of the 20th century. It still seems quietly industrious. There’s a big VA hospital here, and government buildings and agencies. At first glance I see lots of vacant storefronts and empty parking lots, but these are mostly car dealerships. It’s pretty here. There’s a riverfront park, hills all around, a pretty mild climate. I find out later that Roseburg lies in a valley with almost no wind, ever.

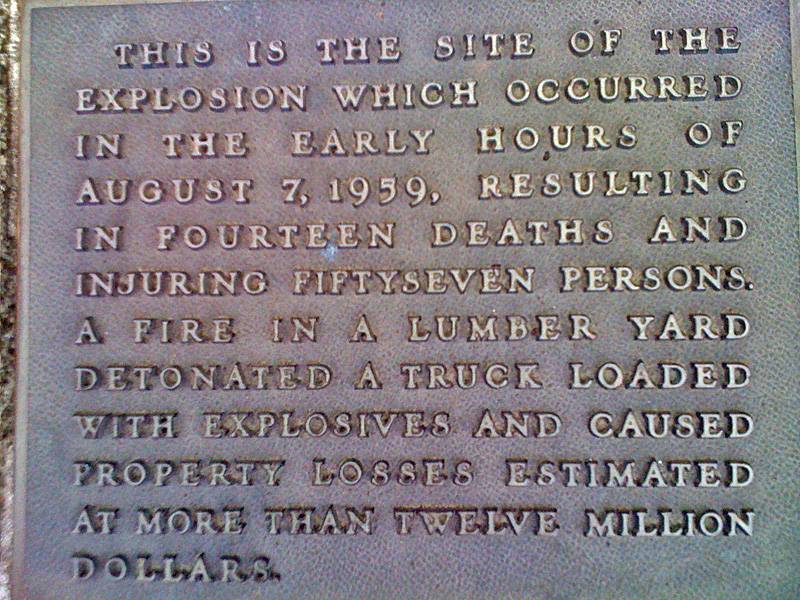

The damage to Ken’s beams happened one stifling August night in 1959. A driver making a delivery of 6 1/2 tons of dynamite and a volatile blasting agent to a Roseburg building supply company the next day parked his truck on a downtown city street. About 1 a.m., a teen-ager driving home with his pregnant wife spotted a fire in a trash barrel outside the building. He rolled it away and told his wife to call the fire department. The ground around the supply company was flammable from years of soaking up solvents and helped feed the blaze. For a time, firefighters used the explosives truck as a shield to protect them from the heat – that is, until someone noticed what the truck was carrying. Moments later the truck blew sky high.

Were it to happen today, people likely would think instantly of terrorism. Back then, what came to mind was The Bomb. A jetliner passing at 17,000 feet saw the mushroom cloud and radioed about a possible nuclear strike. The blast raised an enormous fireball, leveled eight city blocks and shattered every window within two miles. It dug a crater 50 feet wide and 20 feet deep, igniting a firestorm that consumed 45 more buildings outside ground zero. An axle from the truck – and little more of it – was found a quarter mile away, bent in the middle. Fourteen people were kiled, 125 injured, some knocked out of bed by the concussive force. The town’s emergency services took the brunt of the casualties. Outside the Dairy Queen a fireman’s glove was found with a hand still in it; all that remained of a police officer directing traffic was his pants pocket with his keys, discovered a block away. A bolt from the supply store was blasted into a boy’s head. He went into a coma and died a year later. One woman curled up in a ball and survived being blown into a building. A friend walking with her was blown to pieces.

Last August was the 50th anniversary of the blast. The local newspaper published this special section and Oregon public television aired a half-hour documentary. It is riveting stuff. And what it keys on as much or maybe more than the disaster itself, is the aftermath and the recovery – people coming together, individual acts of bravery, triumph of human spirit in face of calamity/tragedy, all very small-town authentic, unstaged. But this is not just a small-town phenomenon. For months after the collapse of the World Trade Center, New Yorkers acted differently toward one another, more neighborly, as if we’d all come through the crucible together. Sure, the good feelings eventually died out and New York went back to its poker-face, in-your-face self, but I don’t think it would take another act of terrorism to bring it back. At least it shouldn’t.

I’ve driven through dozens of towns like Roseburg on this trip, most times coming no closer to them, really, than if I’d been in a jet flying seven miles above them. I landed here by accident, literally. I accepted the forced detour not as fate – I don’t believe in it – but sort of as a chance to do something in spite of myself. There is some reason to be here, something to be learned. Now, at the end of my second day here, my car is fixed and I’m having trouble leaving. I’ve gotten to know this place. I’ve learned its history and glimpsed a little of its soul. I’ve walked around and through it, at first along the major crossing routes that bisect it, and later through the older section of town that was rebuilt after The Blast. It’s a half century old now, a few quiet blocks that remind me of the town in western Pennsylvania where my paternal grandparents lived. The smells are even similar.

It’s 6 pm and the sun has pretty much gone down behind Mount Nebo and its prescient goats. The one-armed cross is glowing again. Ken and I have one last conversation before I say goodbye and pull my car out of his garage. I’ve already decided to stay the night. I won’t gain much time by driving tonight. I want to finish this piece before I leave. And I kinda want to avoid dark nighttime roads for a couple days. The next seven days are going to be solid driving practically. It’s like the calm before the storm, this stop, something to recall fondly if vaguely when the craziness of New York again becomes second nature to me. It’s gotten under my skin somehow, this town. There I’ll be maybe, years from now, on my deathbed, the name on my soon-still lips a riddle to those who hear it: “Roseburg.”

Bill – I’ve read all your pieces now. They are so well written and enjoyable that I would have enjoyed them even if I didn’t know you. The oblique … touch was a great ending, as it was for he who uttered it. Dad